28

How Long Before the Bay is Clean?

The Chesapeake Bay’s waters are constantly contaminated by runoff from both storm-water and agriculture, and the Chesapeake Bay Commission has reported that curbing runoff is one of the most cost effective ways of cleaning the bay.

Yet Maryland lawmakers apparently have agreed to a compromise between builders and environmentalists that will weaken, at least slightly, the state’s new storm-water regulations. The compromise would allow some developments that were already in the pipeline to proceed under the state’s existing storm-water requirements, which are less stringent than the new ones, according to a report by the Baltimore Sun’s Tim Wheeler.

Wheeler reports that the compromise likely will head off more serious blows to the new storm-water rules that had been looming in the Maryland legislature, including a proposal to delay their implementation for up to a decade

Yet it appears there still will be some delays in curbing storm-water pollution, because the compromise will “grandfather” in some development projects and thus exempt them, at least for now, from the tougher new storm-water rules.

Which raises the question, how long will restoring the Chesapeake BayWtake? Lawmakers at one time set 10-year benchmarks for significantly improving the bay’s health. However, after those benchmarks proved to be ineffective because lawmakers failed to meet them, officials recently switched to two-year increments.

The idea seemed to be to hold themselves more accountable –except, it seems, when it comes to storm-water runoff regulation.

28

Chesapeake Bay’s Shifting Goal Line

In so many things written, spoken and published about the Chesapeake Bay cleanup efforts, much of those efforts were directed toward reaching certain goals by the year 2010.

Three months into that supposedly magical year, the bay still faces most of the same problems at the same levels that cleanup advocates sought to rectify by this year.

Recently, the states within the Chesapeake’s watershed, most notably Maryland, Virginia and Pennsylvania, resolved to implement two-year goals rather than the decade-long ones they have previously set forth.

Hwever, not everyone seems convinced the two-year goals will be any more attainable than the decade-long goals.

Tthe Chesapeake Bay Foundation’s Bay Daily blog recently noted that Maryland has not spent much of the money in the Chesapeake Bay Trust Fund raised through a law the General Assembly enacted in 2007. The blog reported that Maryland Governor O’Malley proposed to spend more of the money this year and added:

So let’s at least give Governor O’Malley for moving in the right direction. But now the Maryland General Assembly is talking about cutting O’Malley $20 million in half, to $10 million (or even less), for the upcoming fiscal year.

The cuts would mean lots more pollution flowing into the Bay. And they are also very likely to mean that Maryland will miss one of its first “milestones.”

The blog said the new two-year goals will, if nothing else, lead to more accountability among politicians in the bay states. If voters aren’t satisfied with what their elected officials are doing to help the bay cleanup, the officials could find themselves out of a job more quickly.

However, it will be up to those same voters to pay closer attention to the goals and how states are progressing toward meeting them. If they don’t, citizens and advocates within the watershed will just find themselves frustrated about the lack of progress every two years rather than every 10.

28

Study Says Menhaden Can’t Save Bay

The Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) released a report this month that suggests menhaden, tiny oily fish considered a vital part of the Bay’s food chain, have little effect on the health of the Chesapeake’s waters, according to an Associated Press brief appearing in the Washington Post on March 18.

Menhaden have long been thought to help clean the bay by filtering out nitrogen. But researchers at VIMS found that while menhaden do remove some nitrogen, the tiny fish cannot compete with the vast volume of nitrogen coming into the bay, according to the VIMS press release.

According to scientific estimates, a range of 247 to 585 tons of nitrogen are added to the bay each day. Menhaden, a fish facing a population crisis, can only remove a small fraction.

Researchers watched menhaden in tanks, fed them phytoplankton to see how much nitrogen they could consume, and then made extrapolations about nitrogen removal in the Chesapeake Bay based on the results.

VIMS has been studying menhaden to get a better sense of the fish’s role in Chesapeake ecosystem. More information from VIMS is available at the online research center.

28

Floundering Around – More Limits on Fisheries

As the weather warms up and spring approaches across the Delmarva Peninsula, amateur and professional fishermen and watermen are gearing up to hit the Chesapeake Bay.

However, the struggle between government agencies and those who rely on the bay for recreation or a living has found a new front: flounder.

According to The Daily Times, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Service has decided to shorten the annual flounder catching season from the expected seven months to just five and impose a minimum on the size of fish that anglers can catch and keep.

Fishermen and anglers argue that the season is too short and may not lead to a profitable or fruitful catch in 2010.

The minimum catch size, which this year will be set at 18.5 inches, will bring Maryland in line with neighboring states in the region. Delaware and New Jersey also impose a minimum.

There’s a definite trickle-down effect to consider. As Ocean City baiter Monty Hawkins states in the article, two fewer months of flounder fishing means two fewer months that local tackle and bait shops are open and can do business. That also could affect the number of people who come to Ocean City and other flounder-fishing areas on the Eastern Shore, which could lead to less business at local restaurants, hotels, other fishing-related industries and other seasonal businesses that rely on recreational anglers and fishermen to remain profitable.

28

Md. Dept. of Environment Report Shows Enforcement, Cases Rise

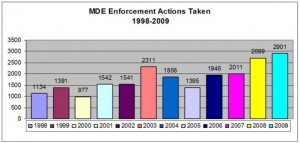

Each year, on or before October 1, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) is required, under Title 1, Subtitle 3 of the Maryland Environmental Article, §1-301(d), to release a thorough report that documents enforcement activities “conducted by the Department during the previous fiscal year.”

The report has been released annually for the past 13 years, and the most recent report covers Fiscal Year 2009, from July 2008 through June 2009. The report is extremely detailed and has a very specific format. It is divided into three sections and in its entirety reflects the performance results for regulatory programs overseeing the environment and the amount of money collected by these programs in the form of penalties. There are 28 areas of enforcement and 15 programs covered in the report (see page 19 of the report).

Most enforcement actions are taken by the Air and Radiation Management Administration (ARMA), the Waste Management Administration (WAS) and the Water Management Administration (WMA). The report defines the regulatory authority of these administrations in the following way:

1). Air: air pollution and radiation programs.

2). Waste: oil control, solid and hazardous waste management, sewage sludge utilization, scrap tire recycling, lead poisoning prevention, natural wood waste recycling, and Superfund remediation programs.

3). Water: This includes drinking water, tidal and non-tidal wetlands, wastewater discharges, coal and mineral mining, oil and gas exploration and production, water appropriation, waterway and floodplain construction, dam safety, stormwater management and sediment and erosion control programs.

Money collected by the different programs (within these three main administrations) in the form of penalties is deposited into seven major state funds: the Clean Air Fund, the Oil Disaster Containment, Clean-Up and Contingency Fund, the Nontidal Wetland Compensation Fund, Hazardous Substance Control Fund (handles identifying, monitoring, and controlling the proper disposal, storage, transportation, or treatment of hazardous substances), money recovered from responsible parties under Environmental Title, §7-221 (covers parties that release or threatened to release hazardous substances), the Sewage Sludge Utilization Fund and the Clean Water Fund.

This year in total, the MDE oversaw 117,421 entities and reported that the total number of enforcement actions taken by environmental programs increased by 7 percent over Fiscal Year 2008. The report also stated that MDE inspected 17% more sites.

Enforcement and compliance actions are separate for the three main administrative bodies, although most regulate through inspections, audits and spot checks. Officials generally allow companies to correct minor violations, but more significant violations discovered after inspection or recurring minor violations leads to penalties, injunctions, corrective orders, or criminal sanctions.

Enforcement and compliance actions are separate for the three main administrative bodies, although most regulate through inspections, audits and spot checks. Officials generally allow companies to correct minor violations, but more significant violations discovered after inspection or recurring minor violations leads to penalties, injunctions, corrective orders, or criminal sanctions.

Penalties collected last fiscal year from environmental violators totaled $6,516,601. This was an increase of $2,546,326 from Fiscal Year 2008. A press release from MDE explains that a “$4 million settlement with ExxonMobil Corporation for the release of more than 25,000 gallons of gasoline at a service station in the Jacksonville area of Baltimore County,” is included in that sum of collected penalties.

Despite these successes, there is an underlying problem expressed in this year’s report: “MDE’s increased enforcement activity has created a much larger workload for the attorneys assigned by the Office of the Attorney General to MDE.” The report compares Calendar Year 2007, in which roughly 340 enforcement cases were referred for legal action with the 816 cases referred in 2009. The report states that because staff cannot keep up with this increase in cases, there were 325 cases that had not been addressed as of January 1, 2010. Furthermore, the report shows that there were 51,587 sites inspected in Fiscal Year 2009 and 157.4 inspectors for all three regulatory administrations.

Graphic Credit: MDE FY 2009 Annual Enforcement and Compliance Report

15

Bay Oysters Fight Another Threat – Poaching

As if the dwindling population of oysters, one of the last natural filters of the water in the Chesapeake Bay, needed another challenge to their survival, they’ve got one.

Maryland’s Capital News Service reported this week that the state government is trying to take strong action to prevent the rise of oyster poaching among fishermen in the bay.

Poaching, the illegal trapping and keeping of wild animals or plants against state or federal regulations, came to light in Maryland again a few weeks ago when two fishers, Zachary Seamen and Edward Lowery, were both charged with multiple counts regarding illegal oyster trapping activity. It wasn’t the first offense for either of them.

The report also says that the number of poaching violations in Maryland has risen each year since 2006, seeing a spike between 2008 and 2009, when the number of poaching charged more than doubled.

There are a lot of things regarding the health of wildlife in the bay (and the bay itself) that will continue to take years to fix. Cleaning up the water, reducing storm water runoff and managing the bustling chicken processing industry aren’t things that can be quickly rectified.

However, poaching seems to be, thanks to the efforts of citizens and politicians alike. Responsible fishermen are looking out after their own and reporting violators to authorities. The number of poaching incidents may have skyrocketed, but so have the number of people caught doing it, which in turn removes them from the water entirely.

12

Can Oysters Survive the ‘Acid Test’?

The National Resources Defense Council is attempting to bring greater attention to rising acidic levels in oceans, which in turn could impact the Chesapeake Bay. According to the Virginian-Pilot, many are worried how the acidity of estuary waters will affect the creatures that live in them.

The documentary film, “Acid Test,” was funded by the National Resources Defense Council and shown in Norfolk this week. It describes how since the Industrial Revolution, “ocean waters have increase in acidity by about 30 percent.”

The Pilot quoted scientists who attended the showing and said they fear higher acidity will hinder the ability of shellfish to make their shells as calcium carbonate in the water decreases. With oysters in the Chesapeake Bay already at record lows, such pH levels may be detrimental to acquatic life, scientists fear. Research being conducted by The Smithsonian Institute supports this concern and suggests that if acidity levels get high enough, oysters currently with shells may see them start to dissolve.

The Virginian-Pilot sad The National Resources Defense Council hopes the film, “Acid Tes” will encourage lawmakers to make changes to help battle rising acidity levels in the water. If the Smithsonian research proves to be correct, it’s a battle that ultimately may be life-or-death for the few oysters that remain in the Chesapeake Bay.

9

‘Broken Promises On The Bay’ Raises Questions

Broken Promises on the Bay is a great read for those interested in learning about the history of the Chesapeake Bay cleanup. Though published in 2008, it still has relevance today.

The article delves into the political side of the cleanup by raising a few pressing concerns:

1) It questioned the government’s commitment to clean up the bay because some analysts found that some reports presented a rosier picture of the bay’s progress than the actual evidence supported.

2) It discussed the government’s failure to create legislation that would address major Chesapeake Bay pollutants.

3) It noted that the governors of Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania met twice and vowed to clean up the Bay — once in 1987, again in 2000. (Last year was the third time the governors came together to vow to clean up the Chesapeake Bay.)

The 2007 GAO’s report on the bay also discussed the issue of the Chesapeake Bay Program’s credibility in reporting on the true state of the Bay’s progress.

The reports also discussed the fact that the Chesapeake Y2K outlined over 101 commitments that the Chesapeake Bay Program was expected to address, some of which the authors knew the program was not going to able to address.

Since then officials have pared down the list of commitments. Yet they still have not achieved the majority of their goals.

There are eleven federal agencies, three states and the District of Columbia providing funding for the Chesapeake Bay cleanup. This combination raises a few questions:

1) How many people rely on the Chesapeake Bay cleanup for employment?

2) How much money is distributed in grants, and initiatives to help clean up the Chesapeake Bay?

3) If the Chesapeake Bay were to ever become healthy and vibrant, how many people would be out of a job?

9

Oysters Have Their Day in Md. Senate

Tuesday is a big day for the Chesapeake Bay’s oysters. The Maryland legislature will hear five bills about oysters alone. And these bills are causing a lot of conflict.

Tuesday is a big day for the Chesapeake Bay’s oysters. The Maryland legislature will hear five bills about oysters alone. And these bills are causing a lot of conflict.

Senator Richard Colburn (R-Eastern Shore) introduced legislation that would hold certain areas of the bay as oyster sanctuaries. His bill states that designation of these sanctuaries would rest with the General Assembly.

Not everyone is happy about it. Currently, the state Department of Natural Resources designates any sanctuary in the bay.

DNR spokeswoman Darlene Pisani said an interview with Gazette.net, “we would not support something that would undermine our efforts to move forward on our oyster restoration strategy.”

But Colburn thinks this is necessary to restore the oyster population.

On his Facebook page, Colburn explains the importance of this bill: “The problem is that those people who make a living harvesting oysters were not included in the decision making of the location of these sanctuaries.”

He says that the General Assembly would protect these interests.

The Senate Education, Health and Environmental Affairs committee will hear testimony from all sides on Tuesday.

Photo courtesy of UMCES.

8

Virginia Elementary School Keeps Bay In Mind

In April of 2009, Manassas Park Elementary School, in Manassas Park, Va., was unveiled with a certification for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED). The Manassas Park Cougars’ new $33 million den boasts innovative methods for reusing water and harnessing sunlight.

Not only is the structure physically eco-friendly, but the walls and floors keep the environment in the minds of students –every classroom is named after a plant or animal native to Virginia and the students walk on floors outlined with images of local wildlife.

Thomas DeBolt, superintendent of Manassas Park schools, touted the new gem of the school system in a story for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, saying, “Every drop of water that falls on this campus doesn’t go into the Chesapeake Bay. It goes in a big cistern, and we pump it back up and use it.” DeBolt said the construction cost would have been roughly the same for a conventional building, which would have required about 50 percent more energy to operate.

VMDO, an architectural contracting company out of Charlottsville, Va., designed the structure, which holds more than 800 students from third through fifth grade. “The highest and best hope we have … is that graduates from this school will be ecological stewards,” said Wyck Knox, project architect for VMDO, in a video produced by the Chesapeake Bay Program.