The Chesapeake Bay Bridge. (Photo by Jason Lenhart - News21)

Chapter 2: How Sick Is It?

An Eastern painted turtle sits near a spray paint can in the Anacostia River. (Photo by Jason Lenhart - News21)

Among the many questions lurking in the policy debates are what it might mean to the Chesapeake region if the bay got sicker—and what the ultimate costs might be if the restoration effort fails.

Many people living in the watershed have no idea how sick the estuary really is, despite decades of political talk, scientific warnings and “Save the Bay” bumper stickers. Ultimately, most people’s experience of the bay is watching it glisten under them as they cross the Bay Bridge on the way to the sandy surf of the Atlantic Ocean.

“I see it in my classes, more and more students who come in and who have never, never been out in a canoe and have no real sense of what’s in the bay or what’s there,” says Mike Lewis, professor of environmental history and head of the environmental studies program at Salisbury University. “And it just does become a backdrop or a setting for waterfront property.”

Scientists know better, because the Chesapeake is a favorite subject for environmental researchers. Saving the bay has become big business.

“More money is spent on the Chesapeake Bay than any other estuary system in the world,” and thousands of scientists are constantly examining one aspect of it or another, says Diaz, sitting in his shaded office in Virginia overlooking the waters of the York River.

Scientists have extensively studied its notorious dead zone, a phenomenon known to scientists as “hypoxia.” It is created when fast-growing algae, feeding on the large quantities of nitrogen and phosphorus flowing into the bay, grow and die in such quantities that they literally suck the oxygen out of the water. The nitrogen and phosphorous come from manure and and other fertilizers that run off farmland, from treated sewage and from atmospheric fallout of emissions from power plants and vehicles. Fish kills, where dozens of suffocated fish float up dead on the surface, are now common.

“The fish can’t breathe at the bottom,” says Beth McGee, a senior water quality scientist with the environmental group, Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

Every year, fish and almost every other life form regularly suffocate across 1,300-to-1,500 square kilometers of the bay, an area that expands and contracts annually with such conditions as weather and pollution.

“The dead zone starts generally at the Bay Bridge and goes all the way down just south of the mouth of the Potomac River,” says Mike Roman, lab director for the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. Although scientists are predicting a smaller oxygen-depleted area this year, overall the size of the hypoxia has been increasing since the 1950s.

Right now, the Chesapeake has the third largest “dead zone” related to human activity in the United States. The biggest lies inside the Gulf of Mexico, the second in Lake Erie. According to Diaz, nearly one third or 31 percent of the Chesapeake is annually hypoxic, compared to 39 percent of Lake Erie, and a whopping 75 percent of the Louisiana continental shelf in the Gulf of Mexico. Because the Gulf embraces deep open ocean, scientists typically measure its hypoxic area against the shelf, or sloping seabed closest to land, for comparison purposes.

Comparisons with the catastrophic oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico are inevitable – both waters have communities that depend heavily on their natural beauty, fisheries and tourism to survive. And both are buckling under man-made pollution.

“Nitrogen is our oil,” says McGee. “If you look at the big picture in terms of resources being degraded because of water quality, we have a dead zone that makes a place where animals can’t live or can stress them to the fact that they are more susceptible to disease, which is exactly what oil does.”

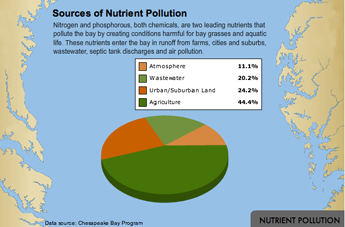

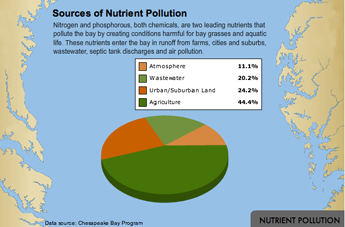

News21 Infographic: Click for full version.

(By News21 designer Stacy Jones)

Pollution seeps into the Chesapeake from many sources. Roughly the largest percentage comes from agriculture, especially animal manure –the hundreds of millions of pounds of it annually generated by the giant farm industry. Animal waste thrown off by the hundreds of millions of broiler chickens and many large dairy operations in the region is laden with nitrogen and phosphorous; some is spread to fertilize crops, some is recycled, and large amounts get carried by rainfall into rivers and then the bay, where it feeds algae and dead zones.

Storm water runoff from urban and suburban development is generally considered the second largest and fastest growing pollution source. As development has boomed throughout the 64,000-acre watershed, paved surfaces have increased, while forests and other natural terrain that used to soak up the rain have shrunk. Now storm water races across all those impervious surfaces, picking up chemicals and other pollutants and flushing them into the bay.

Other major culprits include overflowing sewage treatment plants, seepage from backyard septic tanks and atmospheric toxins from industry and cars.

Their impacts have been extensively studied. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation issued a detailed report last year titled, "Bad Water 2009: The Impact on Human Health in the Chesapeake Region," which said the bay's waters harbor all kinds of bacteria and noxious chemicals that pose increasing health risks to humans.

The dead zones have changed the very nature of the Chesapeake’s waters.

“I remember the creek and the bay used to have such a salty, earthy smell to it,” says Aaron Schultz, who grew up on the water and works as a barista at the Blue Crab coffee house in St. Michael’s, a tony tourist town on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Now when he goes swimming and gets out of the water, he says: “I always smell my arm. You can always smell the water on you, it doesn’t even smell the same anymore, it’s got like a fuel oil smell. It just doesn’t smell like good, clean dirt, you know what I mean?”